Revisiting Ectopic Pregnancy: A Pictorial Essay

Address for correspondence: Dr. Artemis Petrides, 259 1st street, Mineola, New York 11501, USA. E-mail: apetrides@winthrop.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Ectopic pregnancies occur in approximately 1.4% of all pregnancies and account for 15% of pregnancy-related deaths. Considering the high degree of mortality, recognizing an ectopic pregnancy is important. Signs and symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy are nonspecific and include pain, vaginal bleeding, and an adnexal mass. Therefore, imaging can play a critical role in diagnosis. There are different types of ectopic pregnancies, which are tubal, cornual, cesarean scar, cervical, heterotopic, abdominal, and ovarian. Initial imaging evaluation of pregnant patients with pelvic symptoms is by ultrasonography, transabdominal, transvaginal or both. We review the sonographic appearance of different types of ectopic pregnancies that will aid in accurate and prompt diagnosis.

Keywords

Cervical

cesarean scar

cornual

heterotopic

ultrasonography of ectopic pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

An ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the endometrial lining of the uterus. Ectopic pregnancies are estimated to occur in 1.4% of all pregnancies and account for 15% of pregnancy-related deaths.[1] The classic presentation of an ectopic pregnancy is the triad of abdominal or pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, and an adnexal mass. This presentation, however, occurs approximately 45% of the time and has a positive predictive value of only 14%.[1] In the majority of patients, symptoms are usually nonspecific and similar to normal early intrauterine gestation or miscarriage, such as amenorrhea, adnexal tenderness, and cervical motion tenderness. The prevalence of ectopic pregnancies is variable and related to patient population and inherent risk factors.

RISK FACTORS

Ectopic pregnancies can occur in any woman of child-bearing age. However, there are certain predisposing factors which can be additive. Risk factors include a prior ectopic pregnancy, tubal disease secondary to conditions like pelvic inflammatory disease, prior surgery that prevents passage of the zygote or delays the transit time, undergoing infertility treatment, a previous cesarean section, and maternal factors such as, increased age and parity.[1] There is a strong association between infertility and ectopic pregnancy, which is likely due to shared tubal abnormalities.[1] Ectopic pregnancy is also more commonly seen in smokers than in nonsmokers and is likely related to altered tubal motility.[2] The use of an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) is also a risk factor for ectopic pregnancy although lower than with no form of birth control. Pregnancies that do occur in the presence of an IUD have a higher than expected percentage of being an ectopic pregnancy.[3]

LABORATORY FINDINGS

Human chorionic gonadotropin can be detected in the serum approximately 9 days after conception.[2] Therefore, serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) assay is a sensitive test for pregnancy, with a negative test essentially excluding a live pregnancy. A negative level, however, does not exclude the presence of a chronic ectopic pregnancy.[4] There are different reference standards used in reporting β-HCG levels, with the third international standard (IS) and international reference preparation (IRP) being the most commonly used standards. An intrauterine gestational sac should be seen on transvaginal ultrasound when the β-HCG level is 1800-2000 mIU/ml using the IRP standard and by 5 weeks gestation.[24] In a healthy pregnancy, the β-HCG levels should double approximately every 2 days.[2]

IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography form the Gold Standard for evaluating the presence of ectopic pregnancies. Ultrasonographically, the uterus and adnexas are evaluated in sagittal and transverse orientations, which allows for direct evaluation and three-dimensional measurement of any identified extrauterine mass. Such measurements are important for treatment purposes. However, approximately 15-35% of ectopic pregnancies will not have an extrauterine mass identified on transvaginal sonograph.[5] Ultrasonographic examination should also include evaluation for the presence of free fluid by scanning the cul-de-sac, and also around the kidneys, pericolic gutters, perihepatic, and perisplenic areas to assess for a large hemoperitoneum.[4] Color Doppler imaging is also obtained to assess any abnormal flow patterns.[1]

ENDOMETRIAL CHANGES IN ECTOPIC PREGNANCY

An ectopic pregnancy may show some characteristic intrauterine findings. Such findings include a pseudo-gestational sac seen in 20% of patients with ectopic pregnancies (thick decidual reaction surrounding the intrauterine fluid located centrally in the endometrial canal), a trilaminar endometrium (an echogenic basal layer and a hypoechoic inner functional layer followed by a thin echogenic layer representing the interface with the endometrium lumen), or a thin-walled decidual cyst (at the junction of the endometrium and myometrium, seen in normal and abnormal pregnancies).[15]

TYPES OF ECTOPIC PREGNANCIES

Tubal pregnancy

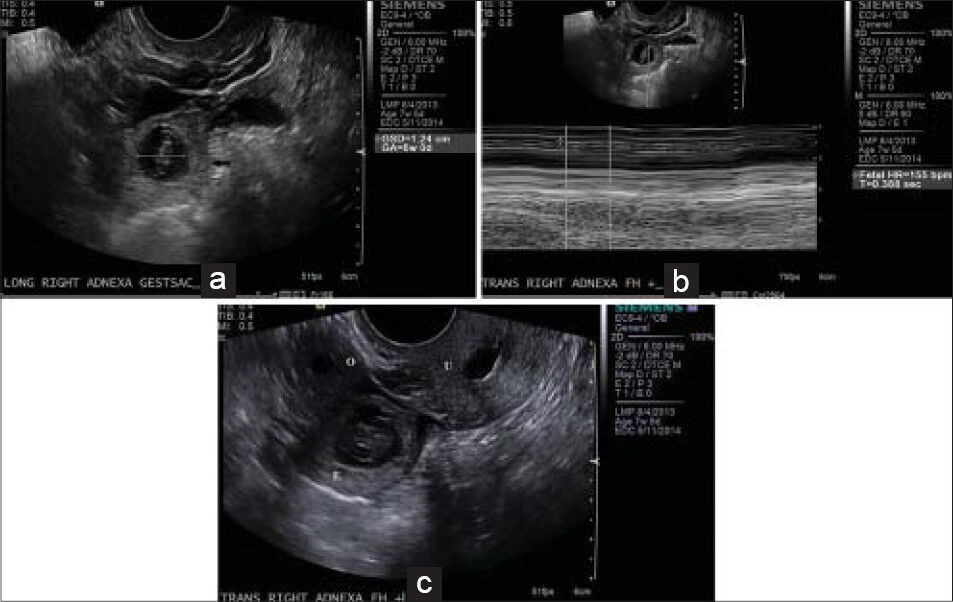

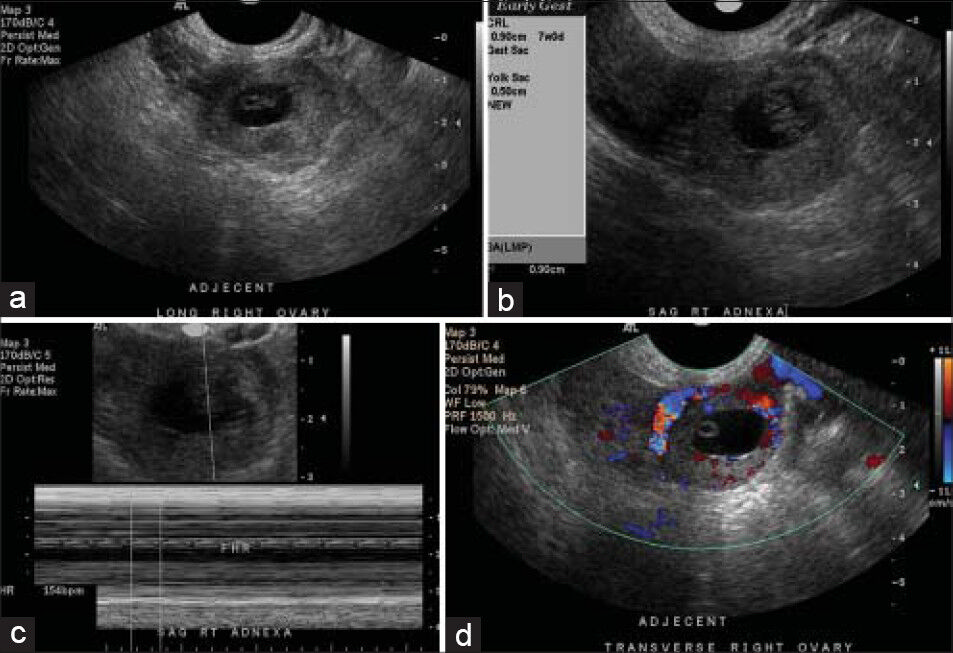

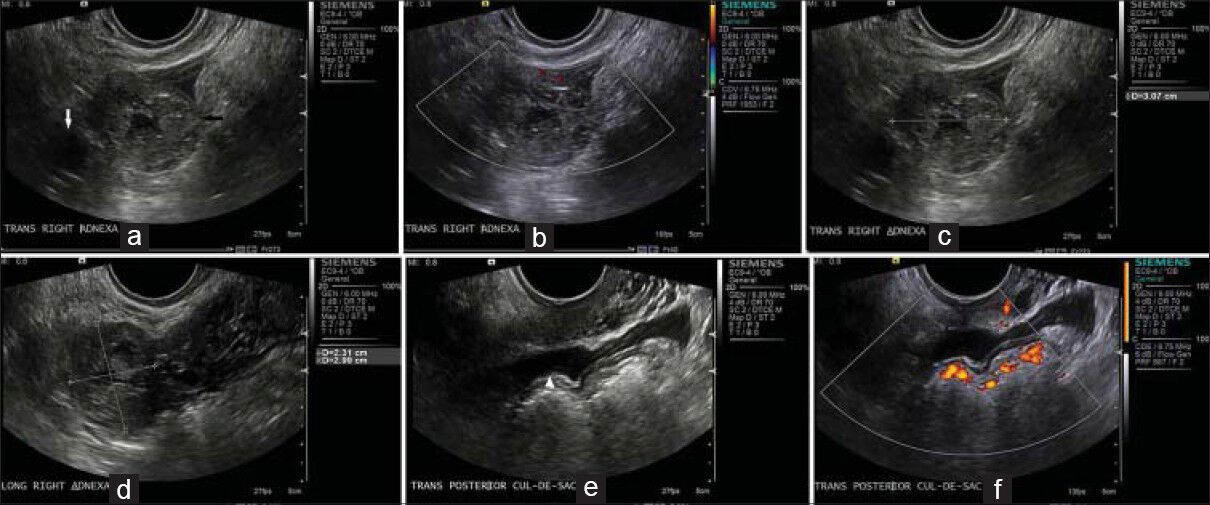

Classical tubal extrauterine pregnancy is the most common type of ectopic pregnancy, accounting for approximately 95% of ectopic pregnancies. Majority of these occur in the ampulla (75-80%) and less commonly in the isthmus (12%) and fimbria (5%).[4] Ultrasonographically, an adnexal mass is identified when it lies separated from the ovary and presents with an independent motion between the mass and the ovary.[1] An ectopic pregnancy needs to be distinguished from any other adnexal mass [Figure 1]. An ectopic pregnancy may have a yolk sac or embryonic material, as well as a common imaging finding described as the ring sign, which is a hyperechoic ring surrounding the extrauterine gestational sac [Figure 2]. Similarly, the ring of fire sign shows peripheral hypervascularity of the hyperechoic ring and represents high-velocity, low-impedance flow surrounding the pregnancy [Figure 3]. The ring of fire sign, however, is nonspecific and can be seen around a normal maturing follicle or corpus luteal cyst [Figure 4].[5]

- 41-year-old female presenting with pelvic pain later diagnosed with ectopic tubal pregnancy. (a-c) Transvaginal ultrasonography images reveal a solid right adnexal mass (black arrow) demonstrating heterogeneous echogenicity and peripheral color Doppler flow which is separate from the right ovary (not included in this image), measures 2.3 × 2.4 × 2.5 cm (b and c). No intrauterine gestational sac is present.

- 32-year-old female presenting with pelvic pain and positive pregnancy test diagnosed with ectopic tubal pregnancy. (a-c) Transvaginal ultrasound images reveal a thick-walled rounded structure (black arrow) in the right adnexa with a yolk sac and fetal pole, compatible with a tubal ectopic pregnancy. (a) Image shows gestational age at 6 weeks with the characteristic ring sign, (b) a fetal heart rate of 155 beats per minute. (c) This structure (E) is separate from the ovary (O), which is located to the right of the ectopic gestational sac with a small follicle, and the uterus (U), which is seen to the left with fluid within the endometrial canal.

- 35-year-old female with positive pregnancy test presenting with pain later diagnosed with ectopic tubal pregnancy. (a-d) Transvaginal ultrasonography images reveal, (a) thick-walled gestational sac in the right adnexa with (b) a gestational age of approximately 7 weeks and (c) a fetal heart rate of approximately 154 beats per minute. (d) There is increased peripheral blood flow characteristic of the ring of fire, findings compatible with a live ectopic pregnancy.

- 33-year-old female presenting with pelvic pain later diagnosed with ectopic tubal pregnancy. (a-f) Transvaginal ultrasonography images reveal, (a) a thick-walled structure (black arrow) containing central fluid and (b) peripheral blood flow within the right adnexa adjacent to the right ovary (white arrow) but separate from it, (c and d) This structure measures approximately 3.1 × 2.3 × 3.0 cm, (e and f) There is a small amount of complex pelvic free fluid compatible with hemoperitoneum (white arrowhead).

Interstitial pregnancy

Interstitial pregnancy occurs when the gestational sac is implanted in the myometrial segment of the fallopian tube in the intramural portion of the tube where it transverses the wall of the uterus to enter the endometrial canal. This is also known as a cornual or interstitial pregnancy [Figure 5]. This is an uncommon site for an ectopic pregnancy, accounting for approximately 2-4% of all ectopic pregnancies.[25] This type of ectopic pregnancy is eccentrically located high in the fundus and not surrounded by 5 mm of myometrium in all planes [Figure 6]. This allows for painless growth and has increased distensibility, which permits longer gestation and can result in pregnancies with as late as 16 weeks gestation.[5] In rare cases, approximately 10 cases reported in medical literature, unruptured interstitial pregnancy has resulted in live births.[6] This type of pregnancy can cause massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage [Figure 7] from the dilated arcuate arteries and veins that lie in the outer third of the myometrium between the thin outer myometrium and the thick intermediate layer. Mortality is twice that of other ectopic pregnancies as rupture can be life-threatening due to its proximity to the uterine artery. Interstitial line sign is an echogenic line that extends from the endometrial canal up to the corneal sac or hemorrhagic mass. It extends into the upper regions of the uterine horn and borders the margin of the intramural gestational sac. The line does not contain any thick echogenic decidual tissue that is confined to the endometrial canal. It does not extend into the intramural portion of the fallopian tube.[1]

- 24-year-old female presenting with pelvic pain and positive pregnancy test later diagnosed with ectopic interstitial pregnancy. (a-c) Transvaginal ultrasonography reveals, (a) an eccentrically located round ring-like mass (black arrow) in the left uterine fundus. Note the thin echogenic endometrial stripe (white arrow) which extends to the inner margin of this mass, (b) It is incompletely surrounded by myometrium and is compatible with a cornual pregnancy. This measures approximately 2.6 × 2.6 cm and (c) demonstrates peripheral blood flow on color Doppler interrogation.

- 28-year-old pregnant female presenting with pelvic pain later diagnosed with ectopic interstitial pregnancy. (a-e) Transvaginal ultrasound images reveal, (a) no gestational sac in the endometrial canal in this longitudinal midline image, (b) there is a gestational sac located eccentrically in the right cornua (white arrow) demonstrated on this transverse image, (c) There is blood flow to the periphery of the gestational sac that contains a yolk sac and fetal pole. (d) The gestational sac is approximately 6.8 mm from the edge of the uterus and (e) shows it is surrounded by a thin rim of myometrium measuring approximately 3.1 mm in thickness.

- 27-year-old female presenting with pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding and a positive pregnancy test, later diagnosed as ectopic interstitial pregnancy. Transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography images show - (a) a heterogeneous mass-like collection (white arrow) in the left adnexa, and in (b) a mass that does not demonstrate internal color Doppler flow representing blood clots and hemoperitoneum. There was no intrauterine pregnancy on evaluation, findings most compatible with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

Cervical pregnancy

Cervical pregnancy occurs when implantation is within the endocervical canal. This is a rare type accounting for less than 1% of ectopic pregnancies.[7] This type of ectopic pregnancy is associated with in vitro fertilization and local cervical pathology related to prior procedures like curettage or cesarean delivery. Ultrasonographically, one can see a gestational sac or placenta within the cervix, a normal endometrial stripe, and an hourglass- or a figure-eight-like structure as the fetus expands within the cervix [Figure 8]. The fetal heart can be detected below the internal os. A cervical pregnancy needs to be excluded from an incomplete abortion proximal to the cervix. There are different imaging characteristics to help distinguish between these two pathologies. In an incomplete abortion, the gestational sac is not adhered to the cervix, it is irregular in contour and shape, and the cervical os is open. This can be confirmed by the sliding sign. The transducer probe can manipulate the gestational sac, confirming non-adherence to the cervix. Cardiac activity may also be detected in a cervical pregnancy with a visible embryo which would not be present in an incomplete abortion.[5]

- 40-year-old pregnant female presenting with pelvic pain later diagnosed with ectopic cervical pregnancy. (a-c) Transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography images show (a) a gestational sac (white arrow) in the lower uterine segment and superior cervix, (b) shows there is a fetus within the gestational sac, and (c) shows fetus with a crown–rump length measuring approximately 4.2 cm corresponding to a gestation of 11 weeks.

Ovarian pregnancy

Ovarian pregnancies occur when the ovum is fertilized and retained within the ovary. They account for 1-3% of all ectopic pregnancies.[45] There is a strong association with IUD usage and it often manifests as a heterotopic pregnancy or is associated with a tubal pregnancy. Ultrasonographically, a gestational sac, chorionic villi, or an atypical cyst with a hyperechoic ring can be identified within the ovary.[5] Bimanual evaluation may be necessary to evaluate a questionable ovarian ectopic pregnancy. If the mass moves separately from the ovary, then it is likely a tubal ectopic pregnancy, while if it moves with the ovary, it is likely a part of the ovary.[2]

Cesarean pregnancy

Cesarean section ectopic pregnancy is implantation within a uterine scar that is separate from the endometrial cavity. This is rare, occurring in 1 in 2000 pregnancies, and accounts for 6% of ectopic pregnancies in women with prior cesarean deliveries.[8] Implantation may have occurred via a wedge defect within the lower uterine segment or a microscopic fistula within the scar. The blastocyst is surrounded by myometrium and fibrous tissue.[9] Ultrasonographically, there is enlargement of the hysterotomy scar with an embedded mass and an empty uterus [Figure 9]. The trophoblast may be seen between the anterior uterine wall and the bladder with absence of myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder.[4] There is risk that the trophoblast will extend beyond the uterus to involve the bladder. There may be thinning anteriorly by compression from the gestational sac, which can predispose the patient to rupture. This can be critical as it can lead to severe hemorrhage and hemodynamic collapse as there is usually prominent vascularity at the implantation site.[5]

- 36-year-old pregnant female presenting with heavy vaginal bleeding for 3 days that slowed to occasional spotting. Patient had a history of two cesarean sections and was later diagnosed with ectopic cesarean pregnancy. (a-c) Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography images reveal (a) a viable gestational sac at the site of previous cesarean scar (black arrow) with a gestational age of 8 weeks 5 days. (b and c) images show the gestational sac is in the lower uterine segment, just superior to the cervix and intimately related to the scar anteriorly (white arrows), MRI d) T2 axial view, (e) T2 sagital view and (f) contrast-enhanced images demonstrate trophoblastic tissue/developing placenta inferiorly with little or no surrounding myometrium (white arrow) confirming scar pregnancy There is some mass effect on the superior aspect of the urinary bladder on the right; however, it does not appear to invade the bladder wall.

Heterotopic pregnancy

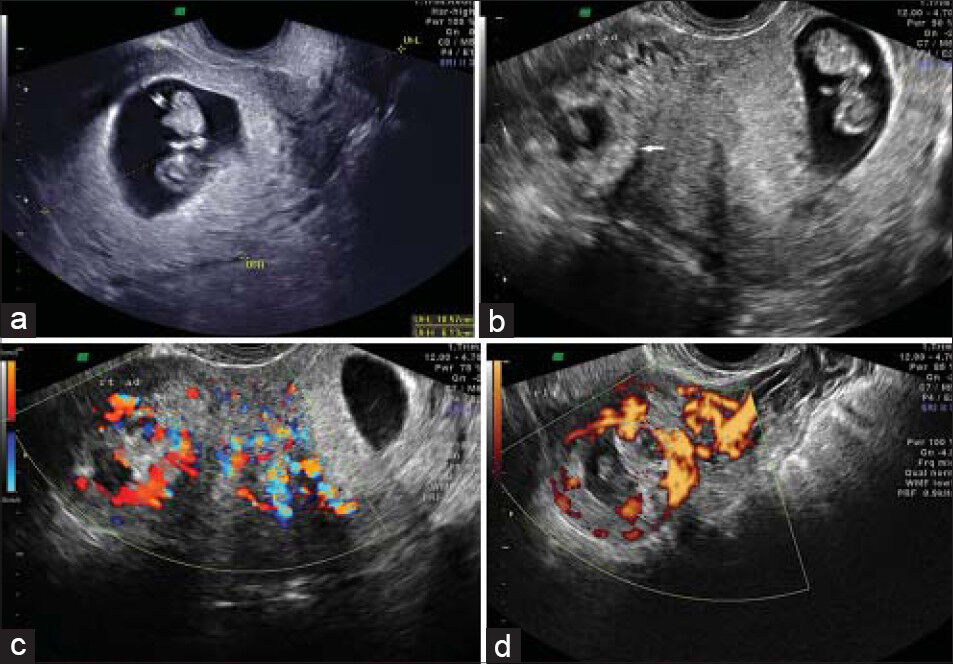

Heterotopic pregnancy is one in which both intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies occur simultaneously. This used to be rare, occurring 1 in 30,000 pregnancies; however, with the increase in assisted reproductive techniques, the overall incidence has increased to approximately 1 in 7000 pregnancies. This is likely secondary to the high prevalence of tubal damage in this population as well as the use of overstimulating medications for ovulation and multiple embryo implantations.[1] Detection of the ectopic pregnancy may be delayed given the presence of a live intrauterine pregnancy. Ultrasonographically, along with an intrauterine pregnancy, a complex mass may be seen in the adnexa [Figure 10]. This may consist only of a gestational sac, or an embryo may be present [Figure 11]. Associated findings may include a large hematoma, hematosalpinx, or fluid within the pelvis.

- 26-year-old female presenting for a second opinion to confirm a heterotopic pregnancy. (a-d) Transvaginal ultrasonography images reveal (a) an intrauterine gestational sac with a fetal pole of gestational age 9 weeks 5 days. There is also a thick-walled ring-shaped structure in the right adnexa (white arrow) compatible with a tubal ectopic pregnancy, (b) image shows the ectopic gestational sac corresponds to 7 weeks 5 days and has a fetal pole, (c) reveals blood flow related to the ectopic pregnancy, (d) the power Doppler image demonstrates the characteristic ring of fire sign.

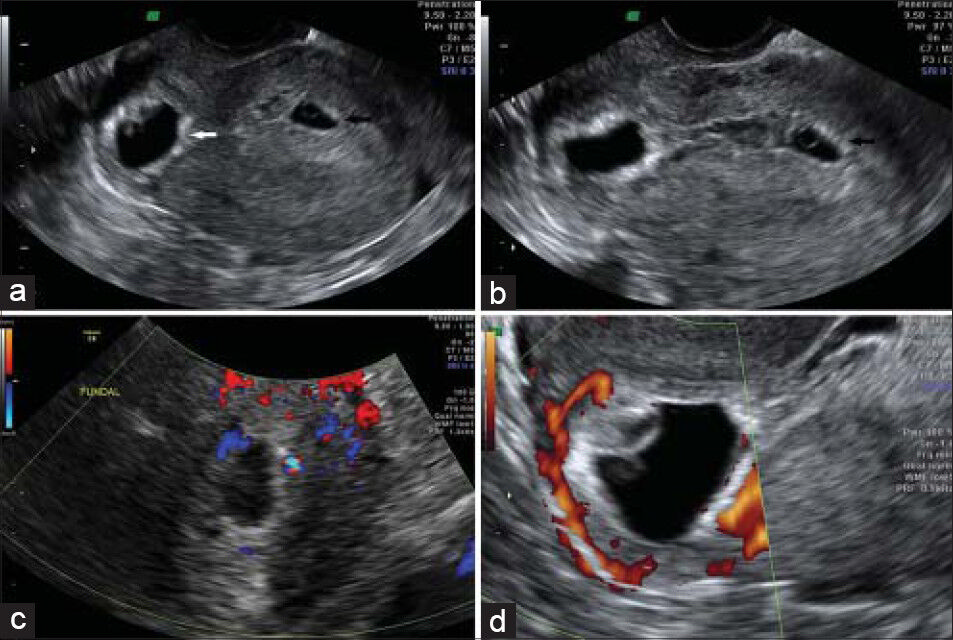

- 40-year-old female of advanced maternal age with a history of prior full-term cesarean delivery presented for assessment of pregnancy was later diagnosed with ectopic heterotopic pregnancy. (a-d) Transvaginal ultrasonography images reveal (a) a retroverted uterus with a gestational sac with a fetal pole and a positive heart rate in the cesarean scar (white arrow) with an estimated gestational age of 5 weeks 5 days, (b) image also shows a fundal gestational sac (black arrow) with a yolk sac, but no identifiable fetal pole with a gestational age of 5 weeks, and (c and d) Color Doppler images reveal blood flow related to the scar pregnancy.

Abdominal pregnancy

Abdominal pregnancies occur when the implantation is within the peritoneal cavity. This is rare, representing approximately 1.4% of all ectopic pregnancies. Risk factors for abdominal pregnancy are pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, tubal damage, assisted reproductive techniques, and multiparity.[10] Sites of implantation include the omentum, pelvic sidewall, broad ligament, posterior cul-de-sac, abdominal organs, diaphragm, large pelvic vessels, and uterine serosa. Blood supply can be obtained from the omentum and abdominal organs.[11] Ultrasonographically, the uterus is empty with a gestational sac seen somewhere within the abdominal cavity, with or without components like a yolk sac or fetal structures.

CONCLUSION

Ectopic pregnancies are estimated to occur in 1.4% of all pregnancies and account for 15% of pregnancy-related deaths. Given this prevalence, a clinical presentation of abdominal or pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, and an adnexal mass in a woman with a positive β-HCG level and associated risk factors should raise the suspicion of an ectopic pregnancy. There are different types of ectopic pregnancies and knowledge of their imaging characteristics is critical in accurate and prompt diagnosis. Imaging modalities useful in diagnosis include ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. The Gold Standard is transvaginal ultrasonography and MRI is being used increasingly as a problem solving tool.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2014/4/1/37/137817

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- The first trimester. In: Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW, Levine D, eds. Diagnostic Ultrasound (4th ed). Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011. p. :1099-110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interstitial pregnancy resulting in a viable infant coexistent with massive perivillous fibrin deposition: A case report and literature review. Am J Perinatol Rep. 2014;4:29-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sites of ectopic pregnancy: A 10 year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3224-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cesarean scar pregnancy: Issues in management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:247-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- The forgotten child: A case of heterotopic, intra-abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy carried to term. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1372-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful outcome of advanced abdominal pregnancy with exclusive omental insertion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:192-4.

- [Google Scholar]